Home

Parent Dinner 2023

Headmaster Jason Robinson delivered this speech to the parent community at the Parent Dinner in January.

It is wonderful to see all of you this evening and a heartfelt welcome to our annual Parent Dinner.

I was talking to a colleague the other day about what I was hoping to address with families in my remarks this evening. He asked whether I was planning to talk about ChatGPT, the new form of generative artificial intelligence that can write essays, answer complex questions, and even compose music and poetry. It’s a topic that has led to hundreds of articles and commentary pieces in the last two months and that a number of families have already written to me about, wondering and worrying how it will affect their sons’ education.

My colleague then joked that I could perhaps ask ChatGPT what I should talk about in my parent dinner address—or even seek its assistance in preparing my remarks.

So I want to assure all of you at the outset that I did in fact write this entire speech myself, without the assistance of ChatGPT or any other artificial intelligence.

ChatGPT notwithstanding, this school year compared to the last two or three years has been blessedly more normal, free of the disruptive and convulsive events we had to navigate since my arrival in 2018. So unlike in past Parent Dinners, where I spoke about the challenges facing boys schools in a post #MeToo world or how to heal our community after a global pandemic, this year I am pleased to report that we have spent the first semester of this school year doing very normal things: teaching, coaching, advising, living together in community, going to chapel, sharing family-style meals together, and working on the implementation of our Strategic Plan, with exciting news in our winter Bulletin about the progress of the Little Sanctuary renovation.

For the first time in my five years at the school, we’ve all had a chance to breathe a bit, to see with renewed appreciation all the things about our community that mean so much to us and that we work so hard to sustain. And we’ve had time to think deeply and ambitiously about new horizons of opportunity for St. Albans to grow and advance our mission—and do even greater things for the boys we are privileged to teach.

I’d like to talk tonight about some ideas that are informing my thinking and that of my Senior Team and our Governing Board about the future of St. Albans: How we see the world right now and how we are trying to prepare our boys to flourish and lead within it.

Indeed, this feels like an important moment of opportunity for us as a community. We are getting our feet back under us after the most difficult periods of the pandemic, feeling more grounded and restored, more secure in knowing that the school we love has been returned to us in its fullness, its traditions intact, its values burnished. And this means we can turn to questions of how we continue to grow, to improve, to do more for our boys.

Our thinking about our future began by returning to first principles. What is most foundational to our mission? What is at the core of our school?

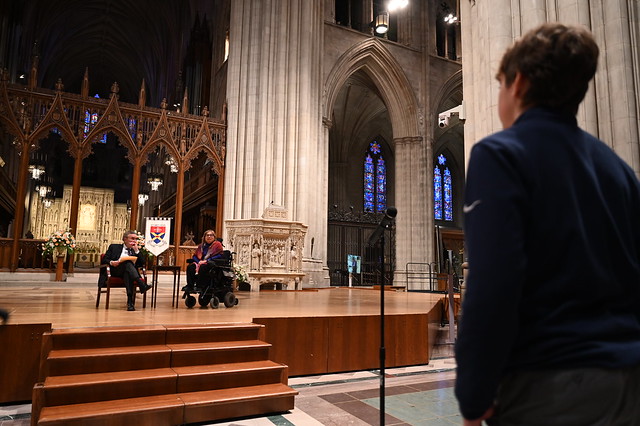

When I talk with boys, families, and alumni, they invariably talk about community, about relationships, about our traditions and rituals of togetherness, about the things we do to build and sustain our distinctive culture. We want to reinvest in these to ensure they stay at the core of who we are. And as my Senior Team, our Governing Board, and I began thinking about all of this, it became clear that the first priority was addressing a longstanding set of needs in the Little Sanctuary to ensure this structure and all that it means to us remains vibrant for current and future generations of St. Albans men. The Little Sanctuary is where we go to be together as a community during periods of celebration and adversity—so coming together around this endeavor has felt wonderfully grounding and restorative for us after a long period of unsettledness in our school and our world.

I’m pleased that the community has responded so warmly to this endeavor—and to the work we are undertaking to strengthen our long-standing commitment to academic excellence by developing a more robust Teaching and Learning Program.

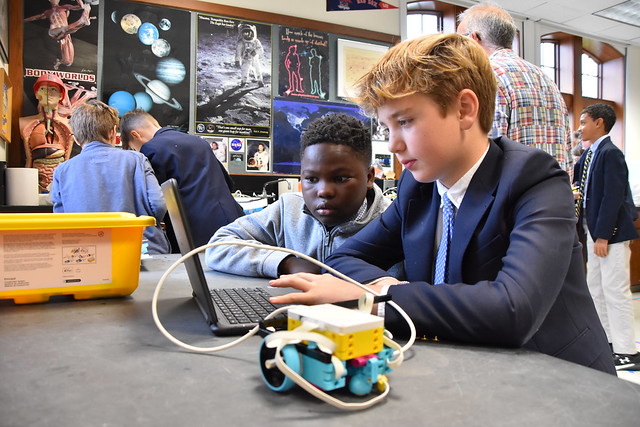

A number of families have said to me: “I know we’re working on the Little Sanctuary, and I think that’s wonderful given that it centers the school’s moral and spiritual commitments at the core of who we are and how we build community. And I love the focus on growing our Teaching and Learning support structures, as excellence in these areas has always been a signature strength of the school. But didn’t the Strategic Plan also talk about Service and Civics education? Didn’t it also talk about the idea of a more interdisciplinary approach to the way we teach, gesturing in the direction of some ideas about more integration of the sciences, engineering, technology, coding, and the arts for our boys? What’s the plan for those parts of the Strategic Plan?”

We are indeed thinking deeply about these topics. Our interest in them arises from certain beliefs that will be central to the education of our boys now and into the future, which I’d like to spend the balance of our time this evening talking about.

We are in the midst of our 10-year reaccreditation, and one of the first things we did as part of this process is review and update our Philosophy and Mission Statements. I asked a group of faculty and senior leaders to lead this effort, and they did a beautiful job. There’s a line in the updated Philosophy statement that is especially important to what I want to share with you tonight and to the future we are working together to build for your sons:

“Grounded in integrity of self and scholarship, St. Albans maintains a community in which boys embrace academic vigor and complexity, celebrate their sense of wonder and joy with others, and understand and value their agency in a world that will benefit from their knowledge, compassion, and character.”

In ways I hope to explain, this notion of helping boys develop and value their “agency in a world that will benefit from their knowledge, compassion, and character” is fundamental to our vision and to what I hope to share with you this evening.

I believe the world our boys will inhabit—as citizens, professionals, and leaders—will be characterized by three fundamental features.

1. Interdisciplinarity

More than ever, the great questions our boys will need to think about and wrestle with are complex, multi-dimensional problems that will require them to synthesize concepts and ideas from many different areas of study. To think coherently about issues like artificial intelligence, advances in bio-technology and genetic engineering, globalization, pandemics, political polarization, climate change, health care, and immigration will require our students to summon many different ways of thinking: Economic, scientific, technological, environmental, ethical, legal, historical. These issues do not fit neatly or conveniently into a single academic discipline, but require dexterity in applying the insights of many different intellectual frameworks to questions that do not have one-dimensional or formulaic answers. If our students are to have agency in this landscape, they must develop fluency with cross-disciplinary synthesis and the complexity this entails. It will be critical to our boys flourishing in future professions and in their future life as citizens.People often ask me what I learned from the pandemic (other than a desire to leave it behind!). As a leader trying to help our community navigate covid-19, I was struck by how essential it was to draw from many different modes of thinking—medical and scientific, statistical, ethical, legal, civic, regulatory, economic, psychological, spiritual. The pandemic was a paradigm example of how a problem of this scale and complexity cannot be solved within the framework of a single idea or single perspective alone. It was, for me, a confirmation of the increasing importance of interdisciplinary thinking in the lives our students will lead.2. Coding, Data Science, and Artificial Intelligence

Code was once an esoteric language understood by few that played a limited role in our lives. Coding is now ubiquitous. It is an increasingly universal language that drives not just the operating systems of our digital devices but the operating systems of almost everything in our world: the way we connect with one another; the way we receive news; the way our economic life is transacted; the shape of our civic life; and with the advent of ChatGPT and generative artificial intelligence, the way we think about writing, education, art, politics, communication, and so much more. Just to understand how the world functions will require an increasingly sophisticated understanding of this background language that drives and shapes so much of our lives. Those who understand the language of code—and the deeper algorithmic principles on which it is based—are the ones who will have agency and mastery in the world, rather than being passive bystanders to these seismic changes.3. Civic and Constitutional Literacy

So many of the complex economic, technological, cultural, and bio-ethical questions our boys will confront in their future lives will lead to societal debates about how best to manage and regulate these forces, to harness their benefits while avoiding their more pathological manifestations. As during prior periods of great transformation, cleavages will emerge, as these technologies will affect different parts of society in different ways. The Constitution provides the civic framework within which we debate these fundamental questions about how to reconcile our enduring values to the emergence—and permanence—of new technologies and the changes wrought by these forces in our lives. Those who understand the Constitution and the civic order it establishes will have agency in this world, will be active participants and leaders within it, and will be able to shape the future to make it serve our common humanity and our enduring values, rather than being carried along as passive consumers of these changes, dimly aware of what is happening and unable to make sense of what it means for their lives and moral commitments.There is yet another dimension to our belief in the importance of civics education. Our boys know that our shared civic life has been under considerable strain in recent years, with a constellation of forces on both the left and the right—both within the United States and beyond—questioning many of the foundational premises that seemed self-evident through much of the late 20th century, when democratic societies in the post-Cold War period seemed to be riding a triumphalist wave of success, captured by Francis Fukuyama’s 1989 article “The End of History?”. Those who understand how our constitutional order came into being—the values it hoped to enshrine, its virtues and its internal tensions—will be able to make sense of the critical perspectives being mounted against it and to be leaders in the regeneration of our civic life, constitutional order, and culture of open, respectful discourse that is the key substrate of our common life in a society where we are constantly called upon to negotiate the differences and disagreements that are endemic to a complex democracy—without falling into rancor and recrimination, without assuming that any one of us has a monopoly on truth or knows the answer to every question vexing our society.

But let me first share a few thoughts about something that perhaps hovers above this conversation.

Some hear the terms “interdisciplinary studies” and “coding” and “STEM” and might say that we should not try to tie education or our curriculum to what they perceive as educational “trends” or “fads.” I’ve had conversations with families in which they’ve expressed some version of the following concern: I sent my son to St. Albans to inoculate him against this sort of faddishness and to ground his education in a rock-ribbed refusal to bend to the false prophets of the new, the people who claim to be speaking for “innovation” but are really introducing thought-viruses into our schools, repealing the traditional liberal arts in the name of progressive over-rotations and new dispensations (well, no one has ever put it in exactly this way, but you take my point).

Likewise, some hear words like “civics education” and “civic engagement” and worry that such notions, however well-meaning, risk introducing contested and divisive political questions into a curriculum that should remain neutral about such matters.

First, some thoughts in response to the concern that St. Albans not yoke itself to fleeting educational trends.

One of the perennial challenges educators face is how a school manages change within itself and in relation to the broader world. A colleague of mine—an alumnus of St. Albans and one of our finest teachers here—said to me recently: “You know, Jason, there really are benefits to the fact that our curriculum of 2020 looks a lot like the curriculum of 1980. A skeptic might say we’re 40 years behind, when in reality, we’ve just avoided 30-year old fads, staying grounded in educational principles that stand the test of time.”

But he was then quick to note that some of the things happening today—like generative artificial intelligence and data science—feel more like fundamental inflection points than fads, more like the internal combustion engine or the creation of electricity. My colleague said: “To not engage with these profound and lasting changes would be negligent for an educational institution, and part of our mission is to be an educational institution.”

I thought this was so wise and insightful, especially coming from someone who is an alumnus of the school and one of our finest teachers.

Building on the insights of my colleague, it is my belief that great schools like St. Albans sustain their greatness by inhabiting two stances:

First, great schools have an enduring sense of what matters to them and why. They derive their strength and their stability from a clear sense of mission and an unwavering set of moral and intellectual commitments that transcend the passage of time. And they vigilantly protect their mission and core values from erosion.

Alongside this is another, second dimension to the life of a school: Great schools are places of deep inquiry and relentless self-examination. They respond with curiosity, not calcification, when they confront new questions. They know that great schools do not stay great by standing still. They hold fast to their mission. But they always ask: How can our mission, which is unchanging, help us engage thoughtfully and adapt to new challenges and opportunities?

When I was a graduate student at the University of Virginia, there was a quotation by Thomas Jefferson, the founder of UVA, that came to mean a great deal to me: “This university will be based on the illimitable freedom of the human mind. For here we are not afraid to follow truth wherever it may lead.”

This sense of inquiry without limits—of fearlessness in thought, of courage in questioning—was so inspiring to me as a student. And it is present each day in our classrooms and in our best moments with our boys. It is a reminder that great schools do not default to fear and limits. We exist ultimately for our students, for the enlargement of their cares and curiosities. And it is their experience—its quality, its depth, its capacity to prepare them for the contours of the world they will inhabit—that is the ultimate measure of everything we do here. For us, thinking about interdisciplinary studies, STEM, coding, and artificial intelligence is not about chasing a fleeting trend. It is about engaging deeply with structural changes in the world our boys will exercise their agency within ... and unburdening ourselves of the fear that such an endeavor will cause us to lose ourselves.

As to the issue of civics education and civic engagement—and the worry this will lead to division and a politicized climate at the school—a St. Albans parent recently shared with me a wonderful article by the president of Princeton University, Christopher Eisgruber, someone I look up to and have learned a great deal from as a fellow recovering attorney who transitioned from law to education. President Eisgruber, like many school leaders, struggles daily with the question of when he should or should not speak about controversial and contested issues in our society, with some urging him to say more and others wishing he would say less.

He notes that at a time when many believe that we are facing existential questions about our basic principles of democracy and constitutionalism, there is a great deal of pressure on leaders to say, do, and engage more—to make civic engagement a larger part of the life of the school. Others worry that, however well-intentioned such efforts might be, a school thereby risks creating what President Eisgruber calls political and moral “orthodoxies” that limit the freedom of thought and exchange of ideas that are fundamental to an educational institution.

In his own struggles with this leadership dilemma, President Eisgruber says he often reflects back on a former Princeton president, Robert Goheen, who led the university during a comparable period of controversy and disruption in the 1960s. Princeton navigated those challenges more successfully than many of its peer institutions, avoiding much of the violence and turbulence that afflicted other college campuses in the ’60s. And a major reason for that was the thoughtful, nuanced stance adopted by the school’s leadership.

Some of Princeton’s alums in the 1960s urged the school to adopt a posture of strict “neutrality” when it came to social, moral, legal, or politically-contested questions. President Goheen, however, always struggled with this idea of “neutrality.” As his successor, President Bowen, once said: “Princeton is a values-laden institution; and it is for this reason that I am reluctant to use the word ‘neutral’ to describe its aims.”

Presidents Goheen and Bowen instead tried to practice what they called “institutional restraint” rather than institutional neutrality. This posture of restraint recognizes that the core mission of an educational institution is encouraging students to think, rather than telling them what to think. For this reason, there will always be a strong presumption against a school leader “taking a position or playing an active role with respect to external issues of political, economic, social, moral, or legal character.” This often disappoints students, faculty, and families, all of whom have commitments and causes they care deeply about and whose lives are touched by the events of our time. For a leader not to speak in these moments can sometimes feel lacking in empathy and unbecoming of someone entrusted with the care of a community. What often appears like a leader’s failure to speak on an external political or social question, however, is ultimately an effort to respect student voice and agency, knowing that when a leader issues pronouncements on a contested matter in the outside world, a leader’s voice can disrupt the process of students autonomously cultivating their voices, their agency. It can disrupt the essential character of a school as a place where we try to get our students to see the world in questions, rather than settled answers and certitudes.

But as President Eisgruber notes, this presumption of restraint is not absolute. Just as Princeton is a “values-laden” institution, St. Albans’ mission emanates from values and moral precepts we are committed to upholding. When there is a “direct and serious contradiction” with a core value of a school, leaders sometimes must speak, sometimes must open the aperture of civic engagement a bit wider. This doesn’t mean school leaders become political activists serving ideological causes. That would be counter to the mission of an educational institution. But it does mean taking seriously one’s moral obligations to students as the leader of a values-laden institution. Sometimes we best serve students and their agency by what we leave unsaid, by not letting our voice overshadow theirs. But we also know that learning, especially the transformative type of learning schools like St. Albans seek to cultivate, happens within community. Underlying the spirited exchange of views and diversity of opinions that course through a school is something we hold in common, a moral infrastructure. For a brief, luminous time, we have the privilege of living and learning together in the same place, becoming part of a shared history that makes us feel invested in one another, as learners and as fellow human beings. Those of us who have devoted our lives to education know that learning is not only about the individual freedom to think and speak, but also the relationships among those doing the thinking and speaking. And leaders are caretakers not just of the intellectual life of their schools but of the relational and moral texture of their communities. When leaders “speak out” in defense of values in this sense, they create the conditions in which student learning and student agency can flourish.

Getting this right is never easy, especially when pressures build and the world continues to feel unmoored. But great schools—the schools that endure—do not default to overly simplistic or binary ways of thinking. They are always trying to balance as judiciously as possible a vision of a school as “simultaneously values-laden and committed to institutional restraint” (Christopher Eisgruber, Princeton University). And it is this balance we are committed to achieving as we work to build a healthy, mission-centered vision of civics education and engagement at St. Albans, one that takes its bearings from what will support student learning and agency in all that we do.

You’ve been a wonderfully attentive audience, and I appreciate your time and thoughtfulness—and most of all the gift of working with your sons. We love them, believe in them, and want the very best for them. We know they are growing up in a profoundly unsettled world with a disorienting pace of change, and we are trying our best each day to ground them in enduring values that will never change, while also making sure they are prepared to lead and flourish in the emerging world they will inhabit--and, in the words of our Philosophy Statement, to “understand and value their agency in a world that will benefit from their knowledge, compassion, and character.”

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to many individuals whose writings and ideas helped to shape my thinking about the topics addressed in this speech: the members of our Governing Board and Senior Administrative Team; the extraordinary group that envisioned our school’s Strategic Plan; the team of faculty members who drafted our new Philosophy Statement; President Christopher Eisgruber of Princeton University; Harvard Law School Professor Randall Kennedy ’73; Rick Melvoin, the former Head of Belmont Hill School; Peter Becker, Head of the Frederick Gunn School; John Austin, Head of Deerfield Academy; the creators of the College Board’s “Two Codes” initiative; Jim Collins, author and researcher; Kevin Mattingly, Dean of Faculty when I was a teacher at The Lawrenceville School; and Ken Ruscio, the former President of Washington and Lee University and former Dean of the Jepson School of Leadership at the University of Richmond. While I am grateful for their influence and inspiration, any deficiencies in my remarks are entirely my own.

St. Albans School

Phone: 202-537-6435

Located in Washington D.C., St. Albans School is a private, all boys day and boarding school. For more than a century, St. Albans has offered a distinctive educational experience for young men in grades 4 through 12. While our students reach exceptional academic goals and exhibit first-rate athletic and artistic achievements, as an Episcopal school we place equal emphasis upon moral and spiritual education.